Walnut Canyon South Slopes Survey

By David Purcell

Walnut Canyon National Monument protects and interprets hundreds of Sinagua culture cliff dwellings, rock art, and agricultural field houses, in a unique convergence of environmental lifezones at Flagstaff’s eastern edge. Up to 600 feet deep, Walnut Canyon contains vegetative associations that are equivalent to the range from the Verde Valley to the uppermost forested parts of the San Francisco Peaks, all of which are prone to natural wildfire, the frequency and severity of which have increased due to exceptional drought and long-term climate warming. The Museum of Northern Arizona collaborated with the National Park Service, Flagstaff Area National Monuments, in an archaeological assessment project during 2021 in advance of a planned program of hazard fuel reduction in the inner canyon and south rim areas.

Project staff completed archaeological condition assessment, fire hazard assessment, and site reevaluation at 137 previously recorded sites, including nearly all of the prehistoric Sinagua cliff dwellings visible from the North Rim and Island Trail. In the inner canyon the crews also surveyed the slopes and ledges below each site for previously unrecorded features.

It is cost prohibitive to carry cut brush (hazardous fuels) out of the canyon, so the NPS plans to scatter it away from sites on canyon slopes and must be sure that no cultural features will be damaged. On the south rim areas, crews resurveyed areas that were initially studied in 1985 and 1987, in part because current standards place a greater focus on documenting low-visibility sites like flaked stone scatters.

What were the project discoveries? First, the fire risk to the sites was variable. Inner canyon sites make up most or all of those identified as high or very high risk for fire, whereas sites on the south rim were mostly low to moderate fire risk. The prehistoric artifact deposits below cliff dwellings typically contain soil with a high organic content that supports dense stands of woody shrubs, pinyon, and juniper that will burn hot, with an accompanying potential for flames to direct plumes of superheated air directly into the alcoves and damage the sites above. Therefore, 97 percent of sites in the inner canyon are recommended for fuels reduction, but only 68 percent of sites on the south rim need treatment. This also reflects the presence of site types on the rim such as artifact scatters that are not considered likely to be affected by wildfire.

Figure 2. Cliff dwelling along Ranger Ledge viewed through a summer downpour

Second, and partly due to very intense monsoon thunderstorms in 2021 (Figure 2), crews noted a lot of water impacts to sites. Fourteen sites showed very recent heavy water erosion in the form of flooding, water pooling, gullying, sheetwashing, or other effects. With three exceptions, these sites are located along Ranger Ledge or around the Island, where water is entering these sites from the sides of the alcoves where the ground surface is higher than in front, and sometimes also coming from the dripline or directly from the ledge in front. Water erosion and gullying also occurred on steep slopes below the alcoves. But water erosion was common among nearly all of the sites examined (104 sites). Although the sites that had experienced the most change in site condition from flooding were located in the inner canyon, sites on the rim also exhibited sheetwashing that had displaced artifacts, even though most of those sites are on level or nearly level ground. Overall, though, 84 percent of the sites are in good condition, reflecting the positive effects of NPS programs to stabilize architecture, remove potential hazards such as fuels, and limit visitor access to fragile places.

Two attributes of the cliff dwellings deserve special notice: the presence of retaining walls and sandstone door coverings. Retaining walls have been noted before, below the cliff dwellings, but inconsistently. This project identified walls at 17 sites, with some having two or three tiered walls. In every case, the walls were built prior to the habitation rooms, and all appeared to have been carefully engineered to level and support the habitations. Some of these remain in pristine condition but some are in danger of collapse and will require stabilization.

Figure 3. Portion of a retaining wall below a cliff dwelling

Walls were sometimes difficult to see, as they were overgrown by the very vegetation the NPS plans to remove (Figure 3). The careful construction of these walls suggests skilled and specialized builders were present who prepared the alcoves for habitation, rather than individual families building their own homes, an idea that has big implications for future investigations of the social structure of Walnut Canyon and the northern Sinagua people.

At least nine of the cliff dwellings contain the remains of large Moenkopi sandstone slabs that appear to have been used as door coverings. The nearest deposit of this material is approximately 2 km away. Tens or potentially hundreds of large sandstone slabs were hauled to dwellings within Walnut Canyon, presumably from that source, indicating the importance of this material to the canyon residents. Although Walnut Canyon is densely vegetated now, following a century of fire suppression, during the peak of its occupation by the Sinagua people the inner canyon and much of the surrounding canyon rim areas would have been stripped of trees and shrubs for use as firewood so wooden doors may have been impractical.

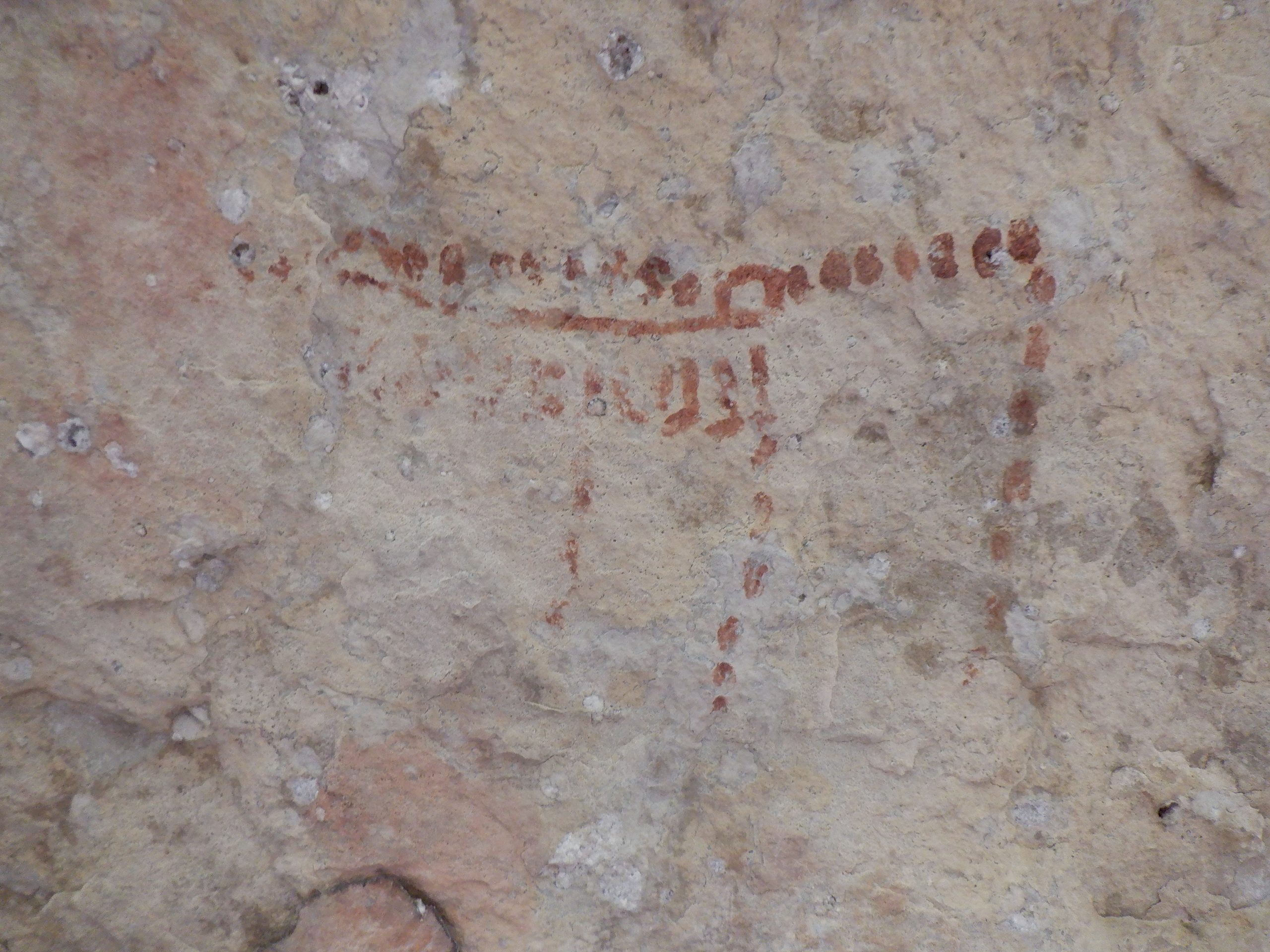

Figure 4. Orange/red Moenkopi sandstone slab mixed with wall stones at a cliff dwelling

Sandstone slabs were flaked and ground to shape to tightly seal against rodents, snakes, and other pests. The real significance of the sandstone is that it is a deep red-orange color that is different from and much more visible than the cream-colored Kaibab limestone or gray Toroweap and Coconino sandstones that form the alcoves (Figure 4). The importance of color in the Puebloan worldview is only now being appreciated. The dwellings of Walnut Canyon were built with limestone blocks set into distinctive yellow-gold mortar, one reason that the cliff dwellings are readily visible from the canyon rim. The use of Moenkopi sandstone doors would have created even greater visibility and the choice of those slabs for doors could be considered one of aesthetics as much as necessity.